It’s time to take the results of our work in previous posts and run them through the meat grinder of time to see what sort of sausage comes out the other end. Will it be a tasty link of brat? Or will it more closely resemble the inedible slabs stuffed into McDonald’s breakfast sandwiches?

Soon, we’ll have the answers we crave. In this entry we’re going to take a look at how we would have fared retiring right before some of the worst downturns history: 1928, 1973, and 2008.

After all, if our plan can withstand those monsters of market suck, it should be able to weather just about anything.

Final Adjustments

Before we get started there are a few things to take care of. First, we’re going to make some changes to the asset sheet listed in Drawdown: Part 1. (During our Strategy investigation we decided to slightly re-tool our holdings to carry more cash in the form of CDs.)

We’re also going to list out a hypothetical asset sheet to account for a different RE scenario. This is because we want to see what might happen if the house isn’t downsized. Finally, we’ll again execute simulations, in exactly the same way we did during Part 2.

Don’t worry, though – we’re going to take care of the adjustment section super quick. No fancy graphics — just tables, lines of description, and sweet, sweet data.

Asset Sheet Update

| Original Asset Sheet | Updated Asset Sheet — Downsize | Updated Asset Sheet — No Downsize | |

| Cash/CD/MM | 30K | 75K | 95K |

| Taxable Accounts | 300K | 255K | 235K |

| Non-Taxable Account A401(k), 403(b), plus Traditional IRA | 250K | 250K | 250K |

| Non-Taxable Account BRoth 401(k), plus Roth IRA | 100K | 100K | 100K |

| Total | 680K | 680K | 680K |

| Spend Rate | 18K | 18K w/1-year increase of 2K | 28K w/1-year increase of 2K |

Notes:

- During the first year of retirement, our spend rate has increased from 18K to a potential 20K due to heath care costs. We discovered during the Strategy section that although health care through the ACA is heavily subsidized, need is determined based on MAGI for the previous year. Since we held employment, we currently have a high MAGI and won’t qualify for aid. This makes health care costs for the first year 2.5K, but in subsequent years it will drop significantly. See the Strategy post for complete details.

- In all cases, I’m holding an extra 10K in cash over my spend rate. This is to cover any emergencies, e.g. health care or vehicle deductibles, flights to other states for weddings and funerals, anything else that might come up.

- A zero-balance HELOC on my residence functions as a secondary emergency fund.

- Owning our current residence costs at least 10K/yr over owning a comparable paid-off place in the town we are targeting for downsize. This makes the hypothetical spend rate 28K if we don’t move.

Re-Running cFIREsim and Monte Carlo Calculators with Adjusted Asset Sheet

| Original Asset Sheet | Updated Asset Sheet — Downsize | Updated Asset Sheet — No Downsize | |

| cFIREsim | 100% | 100% | 72% |

| Monte Carlo | 95% | 93% | 17% |

| Spend Rate as computed against non-cash assets | 2.8% | 3% | 4.7% |

The simulations tell us clearly that a failure to downsize is a likely failure on RE. In fact, these percentages look so poor that I’m not going to bother tracing this scenario through the bear markets. That 28K spend rate is going to make it awfully difficult to navigate through the leaner times.

Moving forward, we will therefore concentrate on the regular Downsize asset sheet only.

Tracing Scenarios – 1929

We’re roaring toward the end of the decade, and there’s a lot of money in our stash, partly because the market has been run up 50% over the previous year. In fact, the market has been so inflated that we’ve suddenly hit our FIRE number and surpassed it, holding 680K in total assets.

We retire on Jan 14, 1929. The Dow Jones Industrial Average is sitting at 295.

During the year, it continues to climb, reaching a peak of 381 on September 3rd.

Then things start going bad. There are rapid, precipitous drops, including Black Monday and Black Tuesday in October. The market finally finds its bottom for the year on November 13th, at 199.

We’re holding almost three years of cash, though, so we’re going to be relatively nonplussed at this point. If you recall, our strategy is to break a CD if the market has dropped more than 10% over the year. And we do our yearly evaluation in mid-January. By then, the DJIA has gone up a bit, to 250. Our non-cash asset pool drops from 600K to about 527K, a drop of about about 13%.

According to the methodology outlined in our strategy section, any drop of 10% or more means we’re going to rely on our cash holdings rather than taking money out of a depressed market. So we break the first of our two CDs and simultaneously cut spending by 20 or so, to 15K instead of 18K.

The following year, we check the market again and there’s been another enormous drop. Our assets are at 428.

We break the second CD and start sweating. We drop our spending to the lowest we can: 12K.

In January of 1932, we are checking our balances again in disbelief. The DJIA is sitting at 88, and at the worst possible time. However, we do still have 9 or 10K left in cash because we cut back on our expenses. This gives us nearly a full year of spending at our reduced rate. So we wait a little longer. We check things again in January of 1933, having completely exhausted any and all cash reserves. DJIA is in the low sixties. According to cFIREsim, our pool of assets is at 263, much higher than you’d expect purely on the drops of the Dow. This is because a) the dollar amounts are inflation adjusted and in this case, we’re in an intense deflationary period, making the assets we’re still holding onto worth much more, b) our bond allocation is helping keep the totals steadier and c) DJIA companies are paying us dividends. So it’s not quite as bad as it looks.

But it’s still pretty bad. And now we absolutely need cash, so we start pulling our core (12K) living costs from our depleted asset pool. I plug these numbers into cFIREsim to generate a fresh calculation and trace the line from 1933.

263,000, 75/25 stock bond split, 12K spend. 46 year RE timeline instead of 50, because we’re four years older.

Note: At this point, we are not working to re-generate our CD ladder because the CAPE is depressed and we think the markets have room to grow.

Somewhat amazingly, this line rides out the entire duration and ends with a portfolio value of 946K in the 1970s. Things are very tight through the entirety of the thirties, though, before the wartime boom of the mid-forties starts to lift all boats. And we’re not exactly living comfortably because spending has been reduced to absolute bare-bones necessities. There’s no question that, without employment, we’d feel like we were hanging on for dear life.

So again, even though cFIREsim computes this line as a success scenario, it’s hard to imagine living through it and feeling like yeah, we’ve got it made, we’re fine. If something similar happens in our own futures, myself and the missus would both going back to work, at least for a few years — assuming we could find jobs at all.

The good news is that five or six years of halfway decent earnings, especially considering our low spending rate, and this problem gets solved.

It’s also interesting to note that our strategy of holding several years’ cash did absolutely nothing to buffer us against the Great Depression’s losses. When incoming waves rise to tsunamic heights, a couple of lousy sandbags don’t do you much good.

For the record, CAPE’s value right before the crash? 26. CAPE’s value today? 26. It hit 7.50 at the very bottom of the depression in 1932.

Tracing Scenarios – 1973

The 1970s were a rough decade for the US domestic markets. I’m not going to go into causes, because we don’t much care about reasons, do we? Nope! We’re most keenly interested in how to cope with the effects of the downturn on our portfolio.

This downturn has a very different signature than the Great Depression. This time, investors were confronted with nearly a full decade of stagnant growth and persistent inflation. Let’s take a look.

Yuck. After the big dip in ’74, even the recovery wasn’t that great — markets reached their pre-dip falls and hung around that level for another eight years, a sequence practically designed to erode stashes.

Since you’ve read through the 1928 saga, you already have a sense for how these things play out, so I’ll pick up the pace by converting data into a table and then subsequently into a graph. In this section I’m going to compare two slightly different plans.

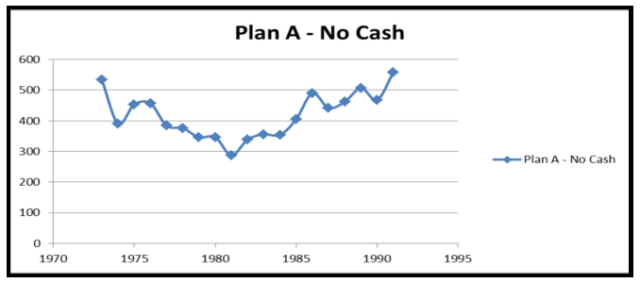

Plan A is to hold all assets (680K) in funds, 75/25 stock/bond allocation, taking out one year of cash each January. These results mirror the cFIREsim output exactly. In this example we take an inflation-adjusted 18K annually without variation.

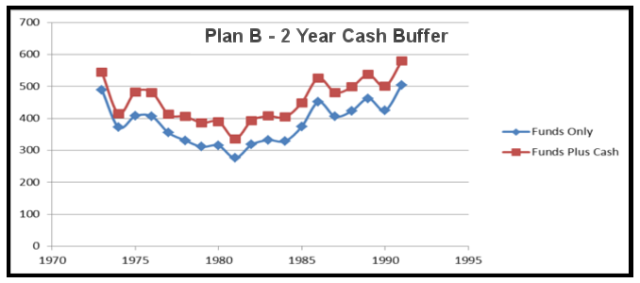

Plan B is our cash buffer strategy. In this case we’re holding 75K of cash and we start our retirement cycle with only 605K in assets. Also, as part of our plan, we will cut back on spending, from 18K to 15K, during years where the market has dropped. These cuts are easily achievable for us and results in only a minor dip in quality of life. Note that this is the same basic strategy that we implemented during our Great Depression example above, and mirrors the strategy from part 3 of this series.

Let’s table it out. I’ll list year-start asset totals along with a few notes for how things were handled during the yearly evaluation period for Plan B.

| Year | Plan A | Plan B Total | Plan B Funds | Plan B Cash | Plan B Notes |

| 1973 | 680 | 680 | 605 | 75 | Retirement Date: Jan 15, 1973 |

| 1974 | 534 | 544 | 489 | 57 | Large market drops. Break CD. Cut spending for next year to 15K. |

| 1975 | 391 | 415 | 372 | 42 | Break another CD. Maintain 15K spending. |

| 1976 | 453 | 482 | 407 | 75 | Markets have recovered somewhat. Recreate CDs from funds. Re-establish 18k/yr spend rate. |

| 1977 | 457 | 481 | 406 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1978 | 384 | 412 | 355 | 57 | Break CD, reduce spending to 15K for following year. |

| 1979 | 376 | 406 | 331 | 75 | Recreate CDs from funds. Maintain 15K spending. |

| 1980 | 346 | 386 | 311 | 75 | 15K spend |

| 1981 | 347 | 390 | 315 | 75 | 15K spend |

| 1982 | 287 | 336 | 276 | 60 | Break CD, 15K spend |

| 1983 | 339 | 393 | 318 | 75 | Recreate CDs from funds. Maintain 15K spending. |

| 1984 | 356 | 407 | 332 | 75 | Spend back to 18K |

| 1985 | 354 | 404 | 329 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1986 | 405 | 449 | 374 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1987 | 490 | 526 | 451 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1988 | 442 | 481 | 406 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1989 | 462 | 498 | 423 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1990 | 507 | 537 | 462 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1991 | 468 | 500 | 425 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 1992 | 558 | 579 | 504 | 75 | 18K spend |

Let’s turn that into some nifty charts that will help us digest this stuff.

First, let’s call our simple no-cash strategy Plan A and see how it looks.

Let’s take a look at our alternate, Plan B.

Finally, let’s take a look at the two of them together:

Although both plans successfully ride out the bear market of the 70s and early 80s, there are some differences between the two.

Difference 1: End Balance Totals

Plan A gives you 558K at the end of 1992.

Plan B will have you sitting at 579K at the end of the same year.

So at first glance, it seems as though Plan B is better. But then, remember, in Plan B we went through 8 years where we cut spending from 18K to 15K for a total drop in spending of 24K over the duration. If we’d spent that money, the totals would be much closer. In fact, at this point, they’d be practically indistinguishable from one another.

Note 1: We only examined the differences in plans through a bear market. During bull markets, Plan A will perform significantly better than Plan B because all assets are in funds, where they can grow. Plan B keeps just over 10% of the totals in cash, which will hurt upward mobility of balances when totals are racing higher. That cash percentage will function as drag on your investments not only because it isn’t invested, but also because cash — even when invested in CDs — typically loses value to the erosion of inflation.

Note 2: Plan B’s balance would have been a little lower than reported above because the cash and CD holdings would have been eroded somewhat over time. I didn’t add this into the calculations but inflation as measured by CPI was averaging 6% during this era. If your CDs were pulling 5%, then you might have been losing another 1% on 75K a year — perhaps $800 or more annually.

Difference 2: Lowest Balance Comparison

Plan A’s lowest balance was 287K in 1982.

Plan B’s lowest balance, in the same year, was 336K, a full 17% higher than Plan A.

If having a low balance makes you nervous, Plan B may provide some real protection.

Summary

We were able to ride out the horrific bear market of the 70s and early 80s without too much trouble, regardless of the plan we used. Plan B (holding a cash buffer) helped us to avoid pulling money out of a depressed market, which resulted in more gentle valuation drops due to poor market conditions.

Individuals can go with either approach. Either way, if you hit a market like this immediately following retirement, you’re going to need a strong stomach. There were several years where our asset totals were below 50% of the amount which we entered retirement with. That’s enough of a drop to make anyone think about going back to work.

Tracing Scenarios – 2007

Ahh, 2007. The housing market bubble had burst and the broader markets hit resistance on growth, fluctuating within a tight range all year.

2008 began fine. In fact, through August of that year, it looked like merely a gentle downturn, the start of a slight correction, and we’d soon be on our way up again. This sort of thing is normal and to be expected.

And then suddenly, something shifted, and it no longer appeared to be just a normal corrective cycle. Late in 2008, massive underlying problems came to the surface: Mortgage backed securities suddenly had no backing because people were foreclosing like gangbusters. Derivatives trading made things worse. Severely overextended banks were distressed. There were bond rating scandals, and cases of insurance fraud.

The bottom fell out in the early part of 2009. The US Domestic stock market shed 50-60% of its total value from peak to trough.

If you want to read a complete play-by-play you can read the first post in this series. Otherwise, in the interest of pushing ahead, I’ll run through the tables-and-charts approach again.

| Year | Plan A | Plan B Total | Plan B Funds | Plan B Cash | Plan B Notes |

| 2007 | 680 | 680 | 605 | 75 | Retirement Date: Jan 15, 2007 |

| 2008 | 642 | 647 | 572 | 75 | Market drops, but less than 10% as of Jan 15, 2008. Don’t break CD, take money out of the market instead. |

| 2009 | 555 | 553 | 496 | 57 | Drop > 10%. Break CD. |

| 2010 | 599 | 634 | 559 | 75 | Replenish cash @36K from market |

| 2011 | 600 | 635 | 560 | 75 | 18K spend |

| 2012 | 618 | 649 | 574 | 75 | 18K spend |

Summary

In this case holding CD buffers provided quality respite against a steep market drop followed by immediate recovery. Additionally, because inflation was very low, there was no real loss of purchasing power in our cash accounts.

Additional Bad Tracks

So far we’ve looked at how we would have fared retiring immediately prior to severe market downturns, and generally things have gone OK.

But a more thorough examination of the results of cFIREsim shows that, Great Depression aside, the very worst years to retire would have actually been in the mid-60s. This is because from 1965 to 1970 there was virtually no growth in the market, and yet inflation crept up at 3% a year or so even as we’re pulling funds out of our stash for COL, eroding the value of our stash prior to the bear market of the 70s.

In these cases, holding cash also would have done virtually nothing to protect us from some very dicey years. Ultimately cFIREsim shows that these scenarios result in success, but it would not have been all that much fun. A 1965 RE date with 680 and an 18k/yr spend would leave you at 227K in 1981 before a gradual and steady recovery saved the day.

Things would have looked fairly grim if you’d been living this scenario out. In reality, you’d be probably be looking for work while simultaneously counting years until eligibility for social security.

Final Thoughts

First off, I feel fairly confident in saying that the Great Depression scenario will probably not happen again. We now have social safety nets in place to keep people spending money and guarding against full-on deflationary feedback loops. The government has learned that spending (through social security and unemployment benefits to citizens) will help to keep the economy running. People immediately spend any money given to them, that money goes back into businesses, and the whole thing holds together.

This is more or less what happened in 2008/2009. Things went to crap, but the government stepped in, extended credit to banks in the form of TARP, extended unemployment benefits, and even passed a halfway decent stimulus package. And it worked. There was a fairly quick, steady recovery, followed by a full-on bull market.

Onto the subject of cash. Holding a CD buffer with a couple of extra years of living expenses can provide peace of mind but isn’t a cure-all for market-related woe. Cash helped in two scenarios (2008, in particular, was a spectacular success) but didn’t in others. It functions as a drag during times of high inflation, and can impede overall portfolio growth because those funds are not in the market. Ultimately holding cash is a luxury that should be considered only after the standard 30X annual spending target has been exceeded.

Example: You need 20K a year to live. 20K x 30 = 600K. If you want to hold X dollars cash, I’d personally recommend you have that amount saved on top of your FIRE number. You’ll notice that this is essentially what we did while working through the above samples.

When you’re holding cash, the greater threat isn’t sudden drops. It’s slow deterioration of spending power followed by a sudden drop and then an unsteady, slow recovery. In these cases, the cash does nothing to fix the root problem, which is lack of real underlying growth. Only growth will save the day in these scenarios, and when it finally arrives, you may have too much in cash to reap the benefits that you need to save your retirement from failure.

For the record, many pros recommend you don’t hold cash. And even my amateurish attempts at tracing through the above scenarios backs up the overall conclusions of these studies — in most cases, it’s better to make your annual withdrawals directly from your funds, rebalance annually, and move on with your life. Holding cash breaks the foundation of the 4% rule which assumes a 50/50 stock bond split.

Still, I’m going to do it anyway. I can afford this plan of action only because I have saved that cash on top of a fairly safe 3% withdrawal rate. Another study, this one reported in the Journal of Financial Planning, notes that at this rate of withdrawal “it doesn’t really matter whether one uses buffer zones.”

I don’t want to die rich. I want to live comfortably and with fewer concerns about money while I’m on this planet. Since I have the buffer available, I’m going to make use of it.

What approach works for you?

Drawdown, Part 3: Strategy << >> Drawdown, Part 5: Validation

I love your drawdown scenarios. I noticed you specifically mentioned three brutal bear markets beginning in 29, 73, and 07. Have you ever created a simulation from 1999-2014. This would include two ferocious 50% S&P 500 drops immediately after two all-time high S&P 500 peaks. Someone retiring in 1999 would have little room for error considering historically low dividends and interest rates for the better part of 15 years.

MDP

Hey MDP.

So, I just ran through this scenario in cFIREsim. Retire in 1999 (pre crash), 680K, 18K spend rate, 75/25 split. This would be the no-cash-buffer strategy. Drops to 482K in 2002, hits 572 in 2006, 401K at the bottom of 2008, and back up to 499 at the end of 2012. Since ’13 was such a good year, and ’14 is also great so far I believe this stash would be about 600 at this time. That’s not all that bad considering that it traces through another essentially lost decade. It might even look slightly better if you followed the cash strategy because you could have ridden out the very bottom of the market in 2002.

Thanks for the info. Those results are much better than I thought. I think the most important point is regardless of your balances and allocations, the ability to dramatically reduce your expenses is the critical component to weathering these different potential storms.

MDP

I completely agree. One of my takeaways from working through these examples is that the ability to be flexible is helpful. If you RE with an already completely bare-bones spend rate and you suddenly want to cut — what do you cut? It’s safer if you go in with enough slack in the system to be able to reduce spending if absolutely necessary.

Superb post! I love how you made it about more than just charts and numbers. I’m especially glad that you discussed the difficulty of actually living out crashes and prolonged bear markets.

Thanks for the kind words and I’m glad this info is of some use. Since I’m close to RE I’m obviously fairly interested in visualizing how things might play out over time. Although we can’t time the markets or predict the future, examining history is a good substitute to help us imagine what might be in store for us. I strongly believe in the power of anticipation – if you are prepared for the worst, you will be ready for whatever comes your way. Note that I’m not exactly expecting the worst… just want to be ready for it, in case 😉

Great job with this series I am loving it! The posts are very helpful, well thought out, and easy to read. I still think I personally will aim to save more and use the cash cushion since one of my goals of ER is to live a semi worry free lifestyle! Thanks for the posts!

Cool, thanks for stopping by. I have one more in this series which is mostly going to be rehash, summaries, and analogies and then I’ll go back to creating less useful content 🙂 Definitely agree that holding some cash will help you sleep — for most people there’s a strong psychological benefit to following this strategy. And if that helps you stay in the market (rather than, say, pulling out and going all into gold or something silly like that) it’s 100% worth any slight drag on your profits when the markets are rising again.

Great series! The concept seems obvious in retrospect, but I don’t think I’ve seen such detailed (and real) scenarios on a personal finance blog before 🙂

Also, thanks for expanding on the cash buffer idea so much in this post. It’s really interesting to watch someone digest the research and then make a call on which way to go (math or psychology, in this case).

Writing this series has uncovered a truth about retirement spending: There’s a ton of information out there about how to grow your pile of money, and how to figure out how much you need to save, but much, much less about actually pulling funds out of your assets to live on. Believe me, if the information I was looking for was readily available, I wouldn’t be spending the time to produce it myself. Not that it isn’t interesting — I just don’t believe in repeating exactly what other people have done. (Also, I don’t quite love spending time in Excel… does anyone?;) ) I’m really hopeful that this series helps save other people some work or at least helps evolve their thinking about how best to approach their own RE. It’s not going to be the same call for everyone.

I absolutely love Excel, but I’m a nerd like that 🙂

Pingback: A Week Of Interesting | Dandelion Cabal

Good stuff aFI. I especially like the realistic insight about holding cash. Back in 2008, I was spending a lot of time on Bogleheads. There were several discussions about why holding cash is a loser, but this is where theory and being human diverge. I was able to stay in the throughout the downturn and recovery (and buy more) because I already had a sizable cash allocation (and no immediate plan to ER). Otherwise I probably would’ve freaked out and bailed after a series of RBDs (really bad day). I know I would’ve struggled to buy back in after the recovery took hold, I’m a big chicken when it comes to recency bias and what feels like an overvalued market. Keep up the good work, your blog is awesome!

Hi EV, thanks for stopping by. I had some of the same issues in 2008 and managed to hold on to my strategy mostly because of the security of employment. Most people I knew were bailing out of the market which I rationally knew was stupid, but there were days where I was tempted anyway. Congrats on being able to hang in there. Recency bias is part of why I went through other bear downturns, too — to see exact characteristics of some other horrible stretches of the market suck. Every time really is different.

I really enjoyed your analysis.

I do have some questions, however…

I am not sure that these simulations show the effects of a cash buffer, as much as they show the effects of having a portfolio with a higher percentage of fixed income/cash (with variable withdrawals) relative to a more aggressive portfolio (with fixed withdrawals.)

Since there are 2 variables different in the study groups it is hard for me to draw any conclusion as to what is driving the changes in portfolio behavior. But my suspicion is that conservative allocations outperform during bear markets. (But I may may just be guilty of confirmation bias, here.)

>>as much as they show the effects of having a portfolio with a higher percentage of fixed income/cash (with variable withdrawals)

Yep, interesting point.

#1: I don’t think your comments are entirely applicable during the steep drop periods (2000, 2008). There’s only 1 year of variable spending (a 3K drop in spending) while portfolio holds its value due to using cash instead of drawing funds out of the market.

#2: Definitely agree with this point re: 1970s simulation. I briefly touch on this in the summary following the ’73 trace. “So at first glance, it seems as though Plan B is better. But then, remember, in Plan B we went through 8 years where we cut spending from 18K to 15K for a total drop in spending of 24K over the duration. If we’d spent that money, the totals would be much closer. In fact, at this point, they’d be practically indistinguishable from one another.” I’d have to run it again without variable spending to get to the core of the question here.

The bottom line is that holding cash PLUS variable spending didn’t hurt — we made it through just fine. Remember, my main goal isn’t to make the most money in the market. It’s to adopt a plan that is effective and reduces daily stress.

Thanks for stopping by, btw, good stuff.

I’m a little late to the party here, but I’m assuming you’ll see this anyway. I have a question about your breaking of CDs and then subsequently replenishing them. It’s my understanding that you’re breaking the CDs to avoid selling any of your investments during a large market downturn, which makes sense. However, I’m getting stuck on the replenishment part. If you break both CDs (or even one), then when it comes time to replenish them, you’re also drawing on your investments for your living expenses, right? So at replenishment time, you’re potentially withdrawing 3 years worth of living expenses at one time — 2 to replenish CDs and 1 to live off of.

Doesn’t this put you at a large disadvantage for tax purposes? Not only would that put you above the 15% bracket and make your long term capital gains taxable, you’d also lose all of your healthcare subsidy. Am I thinking about this right or am I missing something? If this is correct, did you already factor this in and conclude that you’d come out ahead even at the higher tax bracket and lower (or none) subsidy range for one year?

Love the blog btw, both the technical posts like this and the general bitching about work posts. You have a style that speaks to me. 🙂

>>So at replenishment time, you’re potentially withdrawing 3 years worth of living expenses at one time — 2 to replenish CDs and 1 to live off of. Doesn’t this put you at a large disadvantage for tax purposes?

Generally speaking, you’ll be drawing funds out of your Roth, where your principal and conversions have already been taxed and will therefore not be part of the equation when determining your liability for the year. This is assuming, of course, that you have sufficient funds in the ‘principal + conversion’ bucket to withdraw 3 years of living expenses. These funds that you pull from your Roth do not count as income, i.e. these withdrawals do not affect MAGI and will therefore have no impact on any potential health care subsidy.

However, if you need to replenish 3 years and your pipeline has insufficient funds, the story changes. This scenario, if it occured, by nature of the symptoms, would likely be very close to RE. In this case, you may be drawing off of different buckets which are subject to taxation.

A review of the buckets: You can withdraw contributions at any time without penalty, but conversions (ie the “laddered” amounts) are subject to a 5-year hold. Additionally the earnings are taxed until you’re 59 1/2. So if you’re drawing off of either of the second two buckets (immature conversions or earnings) then yes, there’s the potential for a sizeable tax reckoning.

Hi LivingAFI,

Two comments:

1. If I understand things correctly, I think you are a bit off base in your reply to Eric’s comments about the tax impacts of replenishing a CD ladder when you write “and b) potential market growth.” I think your thought process is that the earnings on your Roth IRA pipeline funds will also be available for withdrawal without tax penalty. I don’t think this is accurate. Withdrawals from Roths are defined to be withdrawn in the following order: (1) Contributions, (2) Conversions, (3) Earnings. In other words, if you had convert your $20K from your IRA into your Roth in 2009 and that $20K in conversions had earned another $18K, you would only be entitled to withdraw $20K tax free in 2014, not $38K. The $18K would go into your #3 earnings bucket and would be considered to be withdrawn after your $20K in conversions from subsequent years. In other words, market growth doesn’t increase the amount of money available in your Roth IRA pipeline.

2. It’s hard to tell because it’s a little fuzzy, but your “Kaboom!” graphic looks like it is from 1987, not 1929. That’s a little confusing since in the surrounding text you’re discussing the Great Depression.

Overall though very helpful series of articles, thank you for writing them!

You have a keen eye for detail. The image problem was an administrative error – fixed. Of course you’re also correct on your Roth IRA comments. My response to Eric is a bit muddled, I’ll rework it for accuracy and clarity. Thanks for reviewing, much appreciated.

Pingback: Drawdown, Part 1 : The Basics | livingafi

Pingback: Drawdown Part 3 : Strategy |

Pingback: Drawdown Part 5: Validation |

This is a very interesting series of posts. Why not use your bond allocation in place of the cash buffer? Would the bonds not provide a stable return, even in down times for the equity market, so you could draw down on them (instead of selling equity principal)? And they would provide a better return than cash. These are more questions, rather than statements, as I would think this is the case, but am going purely on theory.

Short answer: Bond funds can also go down for extended periods. And although you can buy some (e.g. MUNIs) directly, then your principal is locked up.

In the end there’s no place to hide – everything has its own risk. I think cash is the least risky, given the purpose here.

Amazing post, like most of them!

I’m devouring your blog, I think it’s one of the best on the internet.

I have a question for you regarding the 4% rule and the scenarios you pictured in these examples.

You never mentioned any potential change in allocation strategy: always 75/25. when you say “withdraw from your portfolio”, I assume you always mean to keep it 75/25 balanced.

Why not consider a withdraw from the bond part of your portfolio in bear market time – and rebalance later? Isn’t it a good hedge strategy, better than keep 75k cash?

I know this is a million years too late, I’ve just recently discovered your blog.

I can’t help but think that the maths is wrong on the 2008 scenario recovery? Plan A has an uplift of $44k from 2009 to 2010 after taking out $18k for living costs. So the $555k earned about 11.2% (ie. [44 + 18] / 555). But Plan B manages to make $63k in growth of invested funds, $36k to replenish your cash position, plus another $18k for living costs. This works out to about a 23.6% return on the $496k funds balance from 2009 (ie. [63 + 36 + 18] / 496). If we use the same 11.2% return, we make $56k on our funds which is enough for the cash replenishment and living costs but leaves our funds still at $498k rather than $559k for 2010.

This makes sense, since the benefit of holding extra cash should buffer your fall rather than boost your recovery (since you would be pulling money out of the market as it recovers). Let me know if I’ve missed something that would make the recovery for Plan B make sense.

It does seem wrong. I no longer have the original data or my work, though, so I can’t trace the process I followed. I do remember acquiring excel spreadsheets from cfiresim showing market values at the end of specific years for the specific run I was tracing. So I was relying on data from cfiresim essentially. I’m leaving your comment so that anyone who reads this and wants to trace through the history and math themselves can go ahead and do so.