I was having dinner with an old friend from university a few nights ago and he expressed disbelief that I was able to retire early.

“How the hell did you pull it off?” he asked, even though he knows damned well I’d been working toward this goal for over a decade. It’s not as though I’ve been keeping the whole FI part of my life a secret from friends. They all knew I’d been striving to eliminate the construct of work from my life.

Simple, I said. The single biggest thing is spending. I just don’t spend money.

“Dude, I gotta say — that’s a pretty shitty answer. It can’t be that easy or everyone would do it. And besides, you’re out with me right now having dinner — spending money — so it’s not even a true statement, dingus. And on top of that, I still remember the unfortunate experience of living with you senior year. You bought all sorts of junk without thinking twice.”

He was right, of course. Because I used to spend a lot of money. In fact, I used to spend absolutely everything I made.

So I found myself digging into personal history to explain the entire transition process in about two hours as he listened and asked questions. This post recounts, approximately, the ground we covered.

Up front, I’ll admit that the spendthrift phase of my personal history is a pretty odd thing to be embedded in the backstory of a frugal-minded early retirement blogger. In contrast, personal hero Mr. Money Mustache revealed that his own past was steeped in the idea of conscious consumption. His parents taught him the basics when he was a kid and he stayed on that path throughout life.

Not me. My own parents were the opposite of well-off. At times, they struggled to make ends meet. They had a bitter, messy divorce when I was 11 which only worsened our financial picture.

And yet, through it all, I could feel them wanting more. My mother in particular often lamented that she couldn’t have a luxury car, couldn’t afford a better and bigger apartment in an upscale neighborhood, couldn’t eat out more often or buy the nicer things at the grocery store. She felt that she’d been cheated out of these things somehow, a birthright denied. (The injustice!)

So you can see that I had absolutely no training in the dark arts of frugality and simple living growing up. Like most people, I was raised by my parents to want shit. To equate stuff with status and happiness. School only served to reinforce the lessons I’d been soaking up at home, as most conversations revolved around how many Transformer action figures you owned. (Yo, I gotz Megatron.)

As pointed out by my friend, I gave this lifestyle a go for quite some time. I spent every dime of the 5K or so I earned over my four years of high school. Then the entirety of earnings through work-study jobs at university. Then, most stupidly, everything I made in my high-paying software/services gig, at least for a couple of years after graduating, even though my alma mater left me with a parting gift of significant debt — an invoice for 42K that had to be paid back at some point. (This was 1999, making that 42K approximately 60K in 2015 dollars).

The thing was, I simply had no interest in paying down debt. I wanted to be happy, and I’d been taught spending was the best way to go about achieving that goal. So I burned through money in a feeble attempt to keep my weary face smiling. Spent, spent, spent.

And yet somehow, despite all of that self-inflicted financial carnage early on in life, I’m here in 2015, at age 38, with no debt, a lean and mean material lifestyle, and no job for all the right reasons, because: Retired Early.

My friend’s question was therefore a good one. How did I do it exactly? I’d been programmed for life to spend everything I made, and then suddenly I turned a complete 180.

How’d I become a saver?

Spending Money

I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess you didn’t buy that throne second-hand, buddy. That shizz looks custom.

Before we get into the transition, it’s worth spending a bit more time reviewing my emotional relationship with money back in high school or college.

And at the time, there can be no mistake about it: Like just about everyone else, I looked forward to spending it.

As soon as my hands touched my paycheck, I’d immediately enter a fantasy world. In this new dimension, I was buying stuff that I thought would make me happy (or at least temporarily distract me from my current set of problems).

It was a two-fer. This sort of daydreaming simultaneously a) rewarded me for the work I’d completed and b) provided a break from reality by imagining all of the things I could buy. Kids, this is called a ‘coping mechanism,’ where you do one thing (sometimes a Bad Thing, like overeating, or drinking) in order to help you deal with another (probably also Bad) thing.

In high school, and perhaps even university, this was fairly harmless, mostly because the dollar amounts were so low. I bought video games, movie tickets, comic books, groceries for the family, a bike and a computer. You could even argue that the video games and computer were investments of a sort — they helped to propel me toward my career in software/IT.

But as I’d mentioned earlier, once I got a real job, I became serious about screwing Future Me over — serious about up-sizing my spending. The first year and a half or so of pulling down a 60K salary, I felt like a sultan with limitless riches. I could buy a car, I thought. A really nice one, too. And then I could get every single album recorded by every single artist ever. Each new idea gave me a new high — thinking about the things I could buy perked my brain up and increased my alertness. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, these were the dopamine-fueled seeds of addiction being sown.

Of course, there was the non-material stuff, too. I ate lunch out at fancy delis. Bought coffees and lattes and other special caffeinated drinks at upscale cafes. Dinner at fine restaurants. And booze anywhere and everywhere, from Irish bars with dark wood imported directly from the motherland (price reflected in the cost of Guinness, of course) to dives with $3 pitchers and back to the higher end, ordering colored drinks in idiotic clubs that ran $15 a pop.

I bought clothes whenever I felt like it. Brand-new furniture. Loads and loads of books, mostly fiction. I signed up for subscription services to magazines (Time, Popular Science, Mad Magazine — whatta combo!) and several of my favorite comics.

And then there were the gadgets. They were probably the worst of it, just in terms of the raw dollar amounts and the tight frequency of purchases. Instead of just messing around with a single computer like I did in college, I bought several. I made a custom MP3 computer dedicated to playing music, and spent 3K on audio equipment to go along with it. I ordered a few 21″ high-end Sony CRT monitors at a time when each and every one ran a thousand bucks. And I’d upgrade everything relentlessly. SCSI hard drive expansions at $400 a pop. New 3D-accelerated video cards for half a thousand. Everything was bleeding edge and awesome.

And I didn’t give any of these decisions a second thought. You name it, I opened my wallet for it. What else are you gonna do with it? Spending is what money is for.

So I pissed my earnings away like this for about two years, from September of 1999 to about the same time in 2001. I blew money like it was my second job, dropping dollars like Dr. Dre drops dope rhymes, or the Duggars drop their gazillion babies out. Or something.

On top of it all, I didn’t think for a second about that college debt, or enrolling in my company’s 401(k). Saving was for boring people, and I wasn’t boring. Nope! Not me! I was going to live it up.

I thought my purchases made me interesting and exciting. They defined me: I like this, I don’t like that, I want this, I need that.

They founded the basis of friendships: What do you like? Where are you going for your next exotic vacation? What are you thinking about buying this weekend? I was thinking about getting the new 3D-Fx board and seeing what kind of frame-rate Quake III spits out on it.

And so on.

Although I was sabotaging my future, at the time, this behavior felt completely all right by me.

Until.

The Event(s)

Although I had an inkling that there was something better I could or should be doing with the money I was making, it took a life-changing event to force me to re-evaluate my patterns.

It took taking on full-time employment for a sustained period.

It took me starting to hate many aspects of my job, to feel the days as soul-crushing instead of interesting or even tolerable.

It took the future-looking visualization of myself in a cube doing roughly the same thing 48 out of 52 weeks every single year for the next four to five decades, from the end of college to my grave.

It took realizing that even if I switched jobs, most of the things I disliked about working would follow me wherever I went. Rigid schedules. Limited vacation. Limitless bureaucracy. Continual reviews and analysis of my performance. And of course, the insistence upon buying into whatever the company’s particular culture happened to be, and subsequently pretending that the whole lot of cray-cray drones in your office are as close to you as your family. In a few of my roles, I was hardly allowed to what I was ostensibly hired to do (nerd-out with technology).

The accumulated weight from these things generated increasing pressure inside of me, like my skin was tightening around me even as my internals were expanding. I felt overstuffed, coming apart at the seams.

These negative developments forced me to reach out, to look for alternate paths through life. I eventually happened upon a tiny subset of humans who were apparently able to get out of the work-restaurant-store-home-work-repeat loop that virtually everyone in the Western world gets mired in. And I found that it was possible to break this loop while simultaneously increasing overall levels of happiness and satisfaction in life.

Put another way, I discovered a group of people who claimed that money and stuff don’t buy happiness.

The crazy thing?

I started to believe them.

Because god knows I was not particularly happy during this period of my life, and I had an awful lot of both money and stuff.

Sidebar Number One

I acknowledge that “The Event” will look very different for many others. It could be a simple recognition that you want to spend more time with your family, perhaps taking a more active role raising your children. Maybe you have a health issue that makes you feel as though your time on Earth is limited and you don’t want to be stuck in the office. Or perhaps you’ve found your true calling — some better way to spend a chunk of your fourscore and ten, but it doesn’t pay much and, well, you’ve got a family to support that won’t exactly appreciate your running away to pursue your lifelong dream of playing the accordion to audiences as large as perhaps seven.

But the point is that many people who get on the retire-early path have an epiphany of sorts which drives them toward alternate paths. This realization gives way to the fact that you have real problem that can only be solved by reconstructing portions of your life.

Sidebar Number Two

After explaining ‘The Event’ to my friend, he spoke for several minutes about his own growing work-fatigue. Then he moved on to alternate dreams. The fact that he’d like to do more travel, while perhaps becoming more heavily involved in a live-action role playing community. (I suggested a bit of goal combination: Fly to New Zealand to check out the Lord of the Rings sets, homemade sword in hand, hacking away at fellow tourists the whole time.)

Point is, I think that many people will eventually have that epiphanal event, which can potentially prompt them to start looking for an alternate path through life.

Work just happened to be mine.

The Problem

During that low period, I was fortunate enough to find a book that outlined my problem exactly. It was called Your Money or Your Life (YMOYL), and it’s now legendary among personal finance bloggers.

I won’t bore you with the details, but after reading it, I clearly saw the necessity of switching from spending to saving in order to open the doors to a new path. It sounds easy, but in reality this is a lot easier said than done because this is not merely a logistics-based challenge, but rather largely a mental one.

The thing is, restricting your spending is not about flipping some kind of magical behavioral switch. It’s not about willpower. If you rely on willpower alone to make life changes, you will generally fail.

Let’s do a diet analogy. If you’re hungry and there’s a chocolate glazed donut right in front of you with nothing stopping you from taking it, eventually — maybe in an hour, maybe in two days, but eventually — you will stuff that treat down your throat. And then you’ll ask for another.

The feelings of deprivation will break almost everyone down, given enough time. It’s best to solve the root problem (the problem of desire) by recognizing that you don’t actually want the donut.

Similarly, I had to realize I didn’t want to spend money. It was merely a habit, and a bad one — one that had gotten me caught in a trap.

So I found ways to convince myself that I wasn’t actually giving anything up. Over time, I steadily converted my thought patterns to believe that my life changes actually resulted in a better life — and not just in the future, but also in the moment — even as I saved.

This isn’t about delaying gratification. If you delay gratification indefinitely, you will feel unhappy. (You will eat the donut.)

You must come to understand — internally, naturally, reflexively, authentically — that spending less money doesn’t make you less happy. That the two things — money, and happiness — are not tightly coupled. The better goal is to seek lasting, sustainable satisfaction in life. To seek your own enough point instead of endlessly chasing more.

And it takes a while to really put the pieces together — to make your new life. You know, the one where you focus on saving and investing instead of spending and consuming. You make a few changes, then you live it for a while and reflect.

You realize: Hey. I’m not less happy. Things are just as good as they were before.

Better, in fact. Because not only has your day-to-day happiness not dropped, you’re also visualizing a more positive future. An end to workplace suck. A chance to travel or try something markedly different with your life. An opportunity to paint and write and dance, or throw yourself wholeheartedly into child-rearing or a charity that means a lot to you. Whatever you want.

You’ve got to learn how to be just as happy not spending money as spending it.

And that there’s your problem.

Not Spending Money Part 1: Logistics

So how do you do it? How do you actually go from your spendthrift life to an alternate existence, one where you’re concerned about every dollar?

There are two main pieces to this challenge. The first is fairly easy — a mere problem of logistics. (Don’t spend money!)

The second, though, is a bit more complicated, as it requires wading through emotional and mental blocks. But we’ll get there a bit later in this post.

So let’s tackle that first part immediately. Consider this a brief practical guide to trimming your outflow.

Step 1: Write All of Your Expenses Down

The very first thing I did was document all of my spending.

All of it.

This is the critical initial piece to starting your journey — you must confront yourself with the numbers.

It’s scary, and it’s painful, and some folks also find it kind of boring because you will need to take out a notebook or phone application to manually record everything. (My dinner companion, for example, was like: Why can’t I just use my credit card statement? This sounds awful!)

Look, although you certainly can use automated services, I strongly recommend that you do manually record everything, at least for the first month or two. If that’s too old-school, at least get some app that forces you to input each expense on your mobile device as it’s happening.

Think of this as part of your training. You must learn to spend consciously, and physically recording the cost of each and every item and service immediately after the transaction occurs helps you to register the event and remember it. You really did just buy a $3.95 croissant at Starbucks. Then, an hour later, you really did go out to Subway to purchase a footlong 11-inch sub, coke, and bag of chips for another $9 before going to a movie for another $15 and following that up with dinner and drinks out for $25 and a taxi home for another $15, resulting in a single day discretionary spend of over $65 — gone, just like that. You are training yourself to spend consciously — to be aware of each and every outflow.

I used a pen and a pad until I stained a pair of jeans with ink, at which point I switched to a retractable pencil. I wielded these tools like a warrior with sword and shield. It sounds corny, but manipulating physical items to jot expenses down in real-time somehow made my actions more real.

You should do this for about two months at first without any changes to your spending. Just do what you do, but record the doing. Pretend you’re an investigative reporter, tasked with figuring out a compelling mystery: Where the fuckitty-fuck has my money gone?

When you’re done, you’ll have a whole lot of data to examine.

Step 2: Compile and analyze

At the end of the month I put together a summary spending report using Excel. This allowed me to see, point blank, my spending choices which, in turn, enabled me to make concrete decisions on where to make changes.

You’ll group things together into spending categories. There’s no hard-and-fast rule as to how you should break things down, but common buckets are rent/mortgage, utilities and media packages, phone, groceries, restaurants, monthly memberships, gifts, transportation, drugs and alcohol, charity, and entertainment.

Be sure to cross reference your pen-and-paper spending notes against credit card statements and withdrawals from your checking account. You don’t want to miss anything in the report.

Once you can see where your money is going, it’s like a floodlight is being shined on your problem. Under the glare, the issues will pop out.

Step 3: Easy Cuts

The questions you will ask as you examine your spending patterns is:

1. Which of these activities actually makes me happy? Why?

2. Are there ways to decrease spending on some of these items without any reduction in happiness?

For example, maybe you spend $1000 a month in groceries for a family of three. I’m pretty sure that makes everybody totally happy. (People gotta eat!)

But are there ways you could cut costs in this area to get the same amount and quality of food, just cheaper? Of course there are. Join a warehouse store like Costco or BJ’s. Ask google for tips.

Or perhaps you have a gym membership at $60 a month that you use, on average, twice every thirty days. Does that make you happy? Is it worth it? Do you really need a gym membership in order to exercise?

There will be some easy fat to trim on your spending. This is the first round of cutting and it’s relatively painless.

Look, a million bloggers have written a million ways to reduce grocery spending or get your exercise in without paying through the nose. Rely on the expertise of people who have gone before you to make your own journey easier.

Go ahead and fix these issues immediately. I did.

Step #4 Identify high cost areas that seem difficult to cut

You don’t have to take do anything about these right away. The first step is to identify and raise awareness of the higher-cost areas so you can start to consider how to (eventually) make changes to bring costs down.

Typical items in this category include social spending (restaurants, bars, flying across the country to weddings), family spending (vacations, loans to a sibling, etc.), vehicle costs (leasing, gas) and housing.

Again, these are areas which you will take longer-term action on. You can’t do everything at once. What you’re trying to do here is establish consciousness of the tough spots.

You can address these one at a time, when you are ready.

Note: I’ve mentioned in the About Me section that it is not a blog goal of mine to provide nitty gritty advice on how to fix these areas, and I’ll stand by that. Pete over at Mr. Money Mustache has written extensively on just about any topic you can think of. For example, I’d mentioned ditching your gym membership. Well, this one might help you to take care of that. Browse the list of All Posts for ideas.

Step #5 Continue to record spending activity and loop through the process outlined above.

It’s common for personal finance bloggers to say: Optimizing is an iterative process.

Let’s unpack that statement a bit. What they’re really saying is: Cut the easy areas first. Then continue to examine your spending patterns for additional ways to trim costs. If you do this over the course of a year or two, you’ll probably be fairly close to your own ideal spending point.

I will add that this point looks very different for various individuals. For some, that might look like 60K for a couple — maybe they live in a high cost of living area, or they have a lot of travel. Perhaps this couple has chopped it down from a starting point of 240K annually — a tremendous drop. Yet, for others, the optimal yearly spend might be a mere 30K for a family of four.

No matter who you are, once you’ve already trimmed a lot, you will eventually find that continued cuts start to really hurt. Maybe that last drop in spending made it impossible for you to pursue a beloved hobby, for example. It’s at this point that you’re probably pretty close to your personal optimization point.

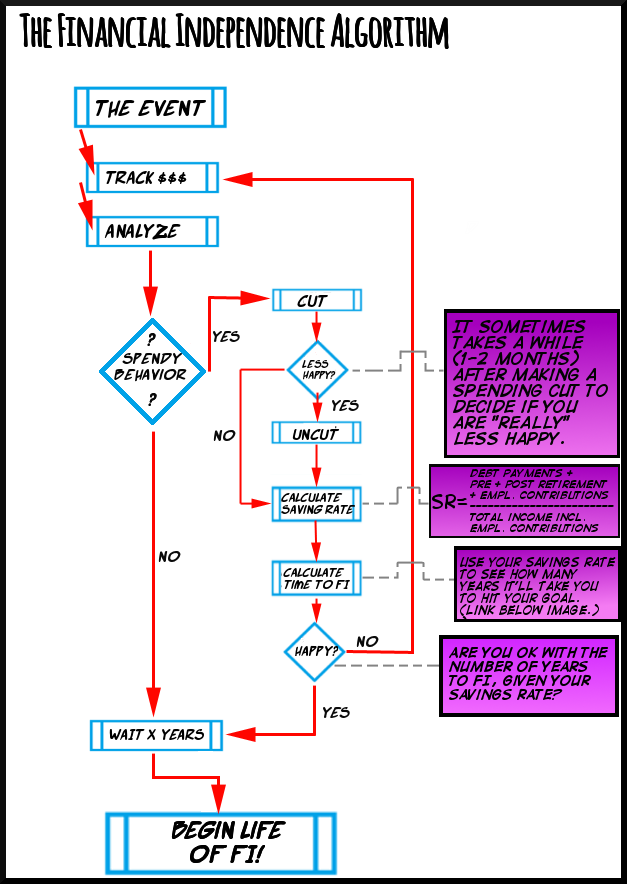

So the (simplified) workflow looks like this:

Protip: To determine your time to FI, use the calculator at networthify.com

Sidebar: Just a bit more on that ‘happy’ evaluation — the one that comes under ‘cut.’

Although I occasionally missed spending money on certain things, I greatly enjoyed saving money for my dream of eventually quitting — and that enjoyment more than cancelled out the little pangs of loss, making the equation a net gain in most cases. Be sure to include any potential increase in happiness from being on the FI path when doing the calculus here. I gained a great deal of pleasure, for example, by telling myself that I could retire months earlier by not spending money on certain things. Put another way, feeding the ER fantasies made me feel really, really good.

That being said, after you’ve waited a while and tried to adjust to your most recent round of trimming, if it turns out that the cut still hurts, it’s time to roll it back.

And honestly, it’s fine to do this. You don’t want to delay gratification forever — it’s important to lead a satisfying life even as you are on your journey to becoming rich and quitting your job early

</end sidebar>

The above is all very rote and instructional, though. Do this, do that, and you’ll save a lot of dough. You’ve probably read variations on this algorithm in a million other finance blog posts.

But that’s where this post is going to diverge a bit from the norm. Next we’ll get into the other side of it — the mental aspects of the transition.

Not Spending Money Part 2: Emotional Challenges

This journey was not easy for me. Personal finance bloggers who have already retired and say that everything was a total piece of cake? Well, although I’m glad that things were simple for them, that isn’t my own story.

Truth is, it was difficult to make the transition, at first. I’m not saying it is for everyone, but it was for me, because I had to kick my addiction to spending. I had to un-learn everything I’d been taught since childhood. And I had no idea how to stop, really, so most of it was trial-by-fire.

Although the internet existed back in 2002 when I started to cut spending in earnest, it hadn’t evolved to the current state. All of the personal finance writers that you read and know and love today hadn’t yet uploaded their first wordpress post. Back then, most people thought that blogging was something you did in the privacy of your own home.

Point is, I didn’t have a whole ton of guidance.

Sure, I knew logistically what I needed to do — move, sell my car, change my purchasing habits and leisure spending — it was difficult to muster the courage necessary for implementation. Some of the changes even felt, initially, like deprivation. I worried that they would permanently alter my overall levels of happiness, or destroy relationships I valued.

So what did I do? I slowly adjusted my thinking. Here’s a few tricks I picked up.

Rule 1: Remind yourself that you are not really saving.

Saving implies putting money aside for a rainy day. You are spending money — on your own future. You are spending money on your freedom. You are spending money to give yourself options down the road.

Protip: Measure your “Financial Independence Spending” in terms of the reduction in time it takes to hit your goal. Use the 25X guideline to make quick calculations. For every 1K reduction in annual expenses, you need 25K less in retirement savings in order to fund a life without actively working. If it takes you twelve months to save 25K, then reducing your yearly expenses by 1K allows you to “spend” money on an extra year of not working. (Awesome!)

Rule 2: Tell yourself that your spending is a choice.

You are actively choosing to solve a problem in your life (e.g. being home for your kids instead of stuck downtown in an office), or pursue a broader interest (e.g. limitless travel). People are happier when they feel they’re in control and so it’s important to remind yourself that your new less-spendy life is something you are pushing yourself toward. You are driving this bus entirely on your own.

Rule 3: Talk to yourself.

Really. This activity is not just for nut-jobs, gutter hobos, and supervillains like myself. It’s a healthy way to build up new habits and solidify positions regarding your actions. Give yourself a personal and continual positive feedback loop. If you just decided to forego a $3 bottle of water at the convenience store because you know you’ll be home in an hour where you can drink limitless delicious DPW tap water virtually for free, tell yourself how proud you are of yourself. Because it’s true. You rock.

Some sample monologue: Yeah, I know I’m a little hungry right now and I’d really like to buy that $6 chalupa from the street vendor but I’d much rather choose to put that money into my investment account where I will eventually spend it instead on more important goals.

Just remember not to move your lips unless there’s nobody else around or you enjoy making other people super-uncomfortable the way that I sometimes do. (Psychopath much? Hell yes!)

Rule 4: Accept your mistakes

You will occasionally continue to spend more than you want.

It will happen. Maybe your significant other pressures you into buying an expensive gift for their parents. Or a friend pulls you out to a classy restaurant where you blow $200 in a single evening on fine cheeses artfully arranged in a semi-circle around a single Neptune Grouper fish imported from the Lost City of Atlantis.

After the event, you may look back with disgust at your behavior and get really angry with yourself, or worse, depressed.

But let me assure you: It’s not all that constructive to beat up on yourself. Tell yourself it’s fine, you understand your mistake, and you will continue to kick ass in the future.

I’m not saying “get over it,” which is generally stupid and insensitive advice. If you spent money needlessly — funds that you really wish you had kept — take a few minutes to examine what happened. Acknowledge the mistake. The bad feelings are telling you that you should pay attention to your recent behavior so that, moving forward, you can improve.

But try to finish that internal chat with the understanding that it’s really no big deal.

Then get back on your saddle and find your path again.

Rule 5: One Major Thing at a Time

Don’t bite off more than you can chew. I strongly recommend that you only make one super-big life update at a time. A few examples of larger scale disruptions:

– A physical move to a less expensive place to live (which is hopefully also closer to your place of work).

– Car related moves (e.g. going from a 2-car to a 1-car family, or downsizing from a Durango to a used Prius or something.)

– Ditching all media entirely, e.g. smart phone and corresponding service plan, cable package, and video game system plus online monthly fees for your favorite games, etc. I list this as a major item because of the considerable, immediate impact to your life: you may not initially know what to do with all of your newly found free cycles. And you will probably need to find some inexpensive or free hobby to fill the gap you’ve just created. Tread carefully here — although definitely work worth doing, these changes can be more disruptive than you might anticipate.

– Related: Selling 98% of what you own in a single weekend to become the One True Minimalist.

– Going from eating almost all of your meals out at restaurants to exclusively cooking at home.

– Dumping that spendy group of adorable friends that makes you laugh like crazy on a regular basis. (Maybe you can take less drastic measures such as trying to convert them to other activities to enjoy together. But good god, don’t remove fun people from your life just because you want to retire early. That’s a pretty bad trade if you ask me. Commit to discovering ways to make things work!)

Try making just one of these big-ticket changes at a time and then giving yourself a couple of months to feel things out, i.e. to become adjusted. Once the new behavior feels pretty normal (usually takes a month and a half or so) then move onto another major item.

Note: The exception to the don’t-do-too-much-at-once rule is if you are in serious, serious consumer debt. Example: Maybe you’re 10K+ in the hole on high interest credit cards. In this case you should do whatever you can to pay that off, absolutely immediately. 10%+ interest rate debt is death to ER plans future planning of any kind.

If things go well, after a short period of time of adjustment, these life changes will leave you feeling awesome instead of deprived. The important pieces of yourself will remain intact — your friends, your family, your hobbies and activities — even as your bank account grows and your sense of opportunity in life soars through the roof.

Messy Personal Stories

Moving

Moving is a big ticket item if you have a family and own a house somewhere.

On the other hand, if you’re single and in an apartment, it may be no big deal at all.

I was in that second category when I first started to save, and I just up-and-moved to a similar quality place with a bit less square footage. I shopped around. Saved $300/mo instantly.

On the other hand, downsizing from a large home to a much smaller one — a process I’ve recently completed — held some serious challenges. Although I’m happy with the move overall, I will not deny that it’s been a large-scale disruption, requiring several months of work along with a fair amount of mental adjustment. (I miss my old kitchen a little.)

Reductions in Eating Out

I mentioned this already — so much that it’s become boring to discuss as well as read probably — but restaurant spending is one of my weaknesses. Although I initially cut virtually everything, after a short period of time I began adding some outings back into the mix so I could retain the same quality of friendships. I don’t know about you but grabbing a casual meal at a neutral location remains one of the most low-key ways to catch up with someone in my book. You don’t have to clear the event with your partner, or clean your house, or worry about what you’re going to serve.

But I did reduce the frequency by only going out when I really wanted to. Example: A co-worker I like a lot with is having a birthday-party lunch at a sushi bar. In this case, not only will I attend, but I’ll also chip in with the rest of the group to pay for her and wish her well. Not a huge deal, so long as I don’t also do this for the co-workers that I dislike — that’s when the costs start to really add up. (On those days, I’ll make up excuses why I can’t do it — maybe I have to work through lunch or I’m training for an upcoming road race and that’s the only time I can get my run in. Whatever!)

Then there’s the after-hours stuff, Dinner and Drinking (the less fun version of D&D). I’ve also gone on and on about this already (holy crap, LAF, stop repeating yourself!) but I can’t resist summarizing: By moving the partying out of bars, the cost of stupidity-filled nights out in my 20s dropped from $50+ to $15 instantly and were no less fun.

Saying No To “Mandatory” Cultural Spending Events

What are mandatory cultural spending events? Glad you asked! I think of these things as stuff people do reflexively because “You just gotta, ya know?” and “Friends and Family Come First” and “YOLO baby.”

Examples include stuff like flying out to remote islands to attend each and every one of your Facebook friends’ weddings regardless of how close these people actually are to you. And/or buying the most expensive items on the gift registry. And/or then buying a bouncy castle for each couples’ inevitable new kid two years later. And/or throwing a 2K birthday party for your own young ‘un when they reach the ripe old age of 1 month.

So this is the part of the blog entry where I reveal myself to be something of a prick (on the off chance that you haven’t figured it out already). Although I have a decent social circle, I skipped a few of my friends’ weddings. To the ones that weren’t within driving distance (~250 miles or fewer), I said fuck-it. Sent a card wishing them well and, in a couple of cases, bought something off the gift registry instead to help soften the blow.

In addition, for a few of the weddings that I did actually attend, I declined participation in the gift registries. Honestly, I don’t like this convention. It doesn’t make sense to me. Let people buy what they really want. Why get involved?

I didn’t expect presents from others for our own wedding — we did not have a gift registry, and we limited attendance to about 30 people, close family, only the best of friends. Why should others expect them from me?

One of my closest friends almost “broke up” with me as a result of my views here. He had a wedding clear across the country and I took a day off from work and booked a flight to attend (at considerable personal expense, I might add). A week later he realized I hadn’t given him and his bride a gift and acted very hurt.

I got pissed. Said: I gave you my presence, and that cost a lot. It was money worth spending because we’re great friends. I also took a vacation day just for you. I don’t understand why you need a physical gift on top of these things. Didn’t you enjoy having me around to celebrate the event with you? Why can’t it just be about spending the day together? How is the vanity gift important? Why is this what you choose to remember, instead of the brilliant and utterly guileless smile plastered on my face during most of the weekend? Or my completely uncoordinated efforts to dance to Rick Astley’s Never Gonna Give You Up with the bridesmaids at the reception?

Then, to drive my point home, I said: Look, my 3-year dating anniversary with my SO is coming up. Why don’t you give me a new set of Martini glasses to help us celebrate? I’ll send you a link to the exact SKU I want from Nordstrom. Also my hamster Gimli The Great is having a birthday in August. I have a registry for him, he’d like a diamond-encrusted water bottle and a years’ supply of premier Argentinian cedar chips to line his cage. Let me know what you’re interested in buying, will ya?

Point being: He’s not the only one who can make shit up to justify being entitled to gifts. Just because our culture says that it’s ‘normal’ to do something doesn’t mean I’m a bad person when I say no to these arbitrarily defined conventions.

The event turned out to be a good opportunity for us to learn something about one another — he eventually agreed the most important thing was my presence and thanked me for being there, and I agreed I probably should have explained in advance that I wasn’t going to buy a $200 registry item instead of quietly not participating. (Also, when I told this particular story, my dinner companion gasped in recognition: I was talking about him. How could I dare?)

Also included in this category might be expensive bachelor/bachelorette parties which require flights to other countries or states and prohibitive spending on clubs, restaurants, escorts, rented limos, buying a wedding ring for your DH/DW worth “three months’ salary” (OMFG that is a shit-tacular level of crazy), baby shower gifts for co-workers (co-workers? Seriously? I can absolutely see something for, say, your sister, but holy smokes, when and how did this become a convention?), annual family trips to Disney World and so on.

I was once asked, at work, to attend a team outing at a massage parlor at the cost of $100 — someone spun it as a relaxing offsite meeting. I couldn’t say no fast enough, laughing uncontrollably at the absurdity of the request even as spittle flew out of my mouth. It’s likely that I included some offensive language in my response. Idiots.

Look, I’m not saying you never spend money on any of the above. But be smart about it. If you blindly follow convention and open your wallet every time you feel it’s culturally expected to do so, you will likely also still be working when you are 65 — just as the culture expects. (I like to say that you can spend money on anything and still reach FI, but you can’t spend money on everything. If travel is your thing, then by all means, go ahead and travel, but you’ll probably need to cut somewhere else [food? gadgets? housing? gifts? charity? and so on] in order to maintain a high savings rate. The trick is to stop wanting to spend money on everything.)

At any rate, the sooner you stop caring so much about adhering without exception to so-called norms, the better. Either that, or stop caring about retiring early.

Choices — we all make them.

De-Gadgeting

I’ll be upfront about this. I found it difficult to stop buying stuff.

I knew I had to. When I analyzed my spending patterns and saw just how much money was going to Amazon and other e-retailers, it was obvious that I had a major problem in this area.

But I was addicted to spending. I mean, it was a part of me. I enjoyed keeping current on technology trends and buying the latest and greatest things. The rush of un-boxing new components for my at-home rigs was intense and undeniable.

Although I stopped cold turkey, more or less, the first three or four months were spent in a state of constant craving. I continued to browse online stores, looking at things that were better than mine. I thought: Wow, that video card has an extra half a gig of memory. Or I’d notice fellow gamers with bigger monitors, faster computers, better network connections, lower ping times. I’d think: That’s why they’re kicking my ass in Unreal Tournament, no doubt. I need to upgrade… upgrade… upgrade…

I was torturing myself, like a recovering alcoholic who goes into a liquor store to look but not swill.

During this initial phase, I admit that I pushed through almost exclusively on willpower. Some days I’d find myself on some vendor’s webpage with six items in my shopping cart, all stuff I desperately wanted, staring at the purchase summary total, just one click away from finalizing the order. I could buy this stuff — right now. It could be at my home in four or five days. Fewer if I select two-day shipping at a cost of only six dollars more.

I sat there, staring at the numbers and the products, paralyzed, caught in between urges. I had to rely on the techniques outlined earlier in the post to get me through. I visualized working for the remainder of my life on the planet simply because I couldn’t stop spending. I reminded myself that this was a choice I was making: I could either a) continue to shop, or b) continue to slog away in an office forever. I tried to estimate how long it took me to save the money I was about to spend — say, a thousand bucks. A month? Was it worth a month in the office to buy whatever it was I was looking at?

Then I’d pace my apartment and force myself to look at the things I’d already purchased. Why wasn’t it enough? That stack of audio CDs on my desk, half of which I hadn’t even listened to — were they making me happy? How about that monitor I’d recently upgraded. Did it make me suddenly walk around with a spring in my step? No. So why did I always want more?

I had to really look inside, to dig deep, to face the power my habits had over me and continually say no, again and again. I had to come to terms even with the very word “happy.” What did people mean when they said that some purchase made them happy, or they “loved” their selection of television, or jeans, or toaster oven ? Did they just mean they use that shit frequently? Or does the affection lie deeper: Are they actively humping those particular items?

What was it about the act of purchasing itself that was so hard to break?

Eventually I came to the conclusion that I would always want to buy stuff on some level — for the novelty, for the distraction of it, for something to do. I personally had to come to terms with the fact that my life, at the time, was fairly empty outside of my incredible spending campaigns. I was trying to fill holes in myself with stuff. (How’s that for uncomfortably honest?)

Although it took me nearly half a year to hit that final realization, months and months of stark i-will-simply-not-buy-this-crap balls-to-the-wall determination, once it arrived, it stayed, thankfully signaling the end to the intense internal conflict. (Later in life, I realized that I was basically “pretending” to be the new, non-spendy person I wanted to be, which is actually a reasonably good way to make major life changes. I faked it until I maked it.)

And somewhere along the line, I began to ask myself different, better questions. Instead of “Why do I want to buy this?” I started asking “What do I want out of life?”

I realized that being surrounded by stuff actually meant nothing to me. This is when, approximately, the changes became permanent. I stopped browsing websites looking for distractions, and started looking for what I really needed, which was to become more immersed in the world and my relationships with the people around me, especially friends and family. To look outside of myself and develop an increased sense of engagement across the board. To relax and accept, both materially and personally, that I already had much, much more than enough.

Suddenly, I found I simply stopped looking forward to buying shit. I recognized internally, at long last, that the stuff was not making me happy. And in the meantime, I’d begun to instead dump more time into activities that did result in genuine satisfaction: increased time spent outdoors, cooking, reading, and exercising, to name a few. I was learning to live real life instead of existing first and foremost as a consumer moron.

And the truth is that the nuts and bolts of real life are ridiculously inexpensive.

Optimizing

So you understand the optimization framework at this point. You look at your monthly expenses and figure out what to work on next, with the goal being continual improvement.

I tracked my monthly spending every month and watched it come down. I looked at the numbers over and over again. I printed copies of the results and posted them in the bedroom of my apartment, allowing me to easily see them each morning. This month I spent $150 less than last month, and so on.

I validated my own behavior, creating personal positive feedback loops. I acknowledged that my quest for financial independence was important enough to devote a fair amount of time to, fully accepting it as a bona-fide hobby and passion.

And I challenged myself to do better. Every month, to do better.

Watching the progress made me feel terrific. When my net worth went positive back in 2003, I began to view my assets in terms of how long I could live off them without going back to work. Got 50K? Well, if you spend 50K a year, that’s only one year of life. But if you spend 25K, it’s double that at 2. At 12,500, you’ve got four entire years away from the grind.

I got carried up in it for a while — the thoughts became more and more exciting as momentum built. I banked raises and the occasional bonus, discovered the library for entertainment and inexpensive community college night classes for learning and growth, found ways to continue to lower food expenses, dumped a Gold’s Gym membership, and so on.

It became a game to play: How to Spend Less and Retire Earlier.

And like most games, once you’re into it, it’s a tremendous amount of fun.

Cooking at Home

So I already mentioned that I changed my patterns to eat at home more often instead of going out.

But initially, I spent an outrageous amount of money on food — around $500/mo. To explain why, I need to briefly delve into my past again.

After I began my first full time job in 1999, I initially bought anything and everything I goddamn well pleased when I went to the grocery store.

And I will confess, I LOVED doing this. I went through a period in my early through mid teenage years where I literally did not have enough to eat at home and took on part-time work to help my family out. I washed sheet-pans over nearly boiling water at a bakery for two years after school instead of pursuing extracurricular activities, and gave about half of what I earned to my Mom, who would in turn buy horrible processed things, pre-packaged rice meals, Swansons TV dinners, Whoppers from Burger King. She was exhausted both from work and being a single mom, which made it difficult to cook full meals every night: like most mothers, she took short-cuts. No complaints, btw – us kids all turned out perfectly fine.

Still, given my upbringing, you can understand that when I finally had enough money to buy whatever I wanted at the market, I couldn’t help myself. The experience was joyful — no hyperbole. I’d walk into the store and instead of loading an entire cart full of Kraft Macaroni and Cheese, I could get anything at all. Yogurt and ice-cream and lobster and fine cuts of beef, real juice, out-of season produce, fresh-baked bread, potato chips, sauces and deli meat, whatever. You get the idea. All of these previously off-limit things were suddenly mine to have.

It was difficult to break out of this particular spending pattern because of the emotional bond I had with food — part of why I spent so much at the grocery store was to convince myself that I wasn’t poor any longer. That those lean years were officially behind me.

But I worked at it anyway, because my monthly expenses didn’t lie: I spent too much in this area for a single guy.

Here’s the short list of things I did to rein in costs.

- First step — and the most important in many ways — Eat Everything You Buy. This means you will learn to cook from what you have on hand, rather than what you want in the moment. You won’t go to the grocery store until your refrigerator has already been raided and there’s not much left. Once you’re no longer throwing anything out, you will automatically get more meals out of the food you purchased. This is a pretty big deal, actually — wasted food costs the average U.S. family about 2K a year. (You’d need a whopping extra 50K in your retirement stash to cover this!)

- Second step: Learn to, like, actually cook. Don’t be afraid, just dive in. Immediately go buy The Joy of Cooking – the book costs very little used and has quality recipes for practically anything you can think to make.

- Third: Start going to cheaper markets. Shop around and perform some cost evaluation to see if it’s worth it. Maybe Costco is right for you. Or that local Asian food market. I live in the Northeast of the United States and by far the best place to go around here is Market Basket. They have exactly the same items for sale but everything is 20-30% less than competing stores. Amazing. Once I discovered this I literally stopped going anywhere else. Even Sam’s Club and Costco aren’t any better for most items, and I don’t have to buy in bulk and then worry about how I’m going to Eat All of the Things before they spoil.

- Third step: Adjust diet to eat less expensive stuff, especially for your throwaway meals, like if you’re eating alone that night or bagging something to be hastily consumed in the office between meetings. Note that I am not advocating sabotaging your diet or health for the sake of saving a few bucks here and there (e.g. ordering off McDonald’s Dollar Menu on a regular basis) — that is simply a shitty, stupid trade-off. You can eat inexpensively while avoiding processed foods and maintaining quality. Do some research and find an approach that works for you and yours.

- Fourth step: Learn to buy seasonal items. Apples in the fall. Pomegranates and chestnuts in the winter, oranges and asparagus in the spring. Seasonal items are both cheaper and taste better. Load up on luxury fruit (cherries, grapes) in the warmer months. In the dead of winter, avoid these things. Most of the time fruit ends up tasting like garbage in December anyway because it’s been imported from halfway across the globe and is no longer exactly fresh.

- Fifth step: Cook from staples. It sounds horrible, like you’re about to put some bits of metal from a Swingline into a pot to boil, but I promise, it’s okay. Staple = source of healthy carbs, e.g. potatoes, rice, beans, pasta. Despite all of the stuff on the news about carbs being bad, the truth is that in moderation, they’re an important part of most peoples’ diets. You add a sauce or a spice, a bit of meat or other toppings and sides to these things, and you’re good.

For a long time, my staple of choice was rice. I bought a pressure cooker on the advice of an Indian co-worker who noticed I’d begun to bring my lunch to work. He was like: You have to start cooking rice. It goes with practically everything and is a good change from pasta. Cook brown and it keeps you full for a while. (Right on all counts.)

I bought in bulk – rice stores well. I stir-fried vegetables on top of it. If I made something like chili, sometimes I’d mix it in directly, making a wicked goulash and stretching it out. Amazing.

I also allowed myself to “cook special” for things like visits with family, friends etc. So we’d let loose a little and buy a wider variety of items. The best part about only doing this once in a while is that it really feels like a treat to, say, buy scallops, New England clam chowdah and swordfish along with fresh artisan bread and a $15 bottle of wine. You’ll remember the event.

As my cooking skills grew, my sense of deprivation disappeared. In fact, after just a few months, I started to feel the opposite: Eating out kind of sucks. It has the potential to take a lot longer than preparing your own meals. Then there was the increasing evidence that most of the stuff I made at home tasted better than your average chain. Plus, there’s just no getting around the fact that at a restaurant, you have to wear pants, or shorts at the very least. Like, without exception. This sucks.

Look, food is one of the greatest, most consistent daily pleasures that we all have in life. Don’t do anything rash like moving to soylent or attempting to subsist on a diet of potatoes and multi-vitamins indefinitely (like the marooned astronaut protagonist from The Martian) just to save a few bucks a month. Enjoy your meals, folks. Just be creative and cost-conscious about how you do it.

I’m Not Up In The Club(s)

I lived in San Francisco in my early 20s, and there existed some amount of pressure for folks in my age bracket to frequent nightclubs, complete with long lines to wait in, door fees, and $15 drinks.

I observed any night out involving these sorts of excursions ended up running at least $100 a pop. And it was never even remotely worth it. (Truth was that I actively disliked the whole environment — dancing, tons of insecure strangers who were uber-focused on appearance and likely high, music so loud you can’t talk to anyone, and so-on.)

So I just stopped going. This was one of those wonderful cases where being frugal pushes you to finally stop doing something you didn’t want to be doing anyway. I mean, when I saw just how much money I was blowing just so I could stand close to energetically gyrating strangers for a few hours before waking up abysmally depressed and hung over (or worse) I realized that putting a halt to this behavior was a true win-win: Saving money, while simultaneously cutting out something awful in my life that provided absolutely no benefit whatsoever.

Besides, I can feel socially awkward practically anywhere — there’s absolutely no need for me to spend money for this privilege. I’m a geek, after all. That feature was included in the original equipment.

Become So Busy You Can’t Spend

If you read this blog at all, you know I had a few employment experiences that were a little rough.

Two in particular (FinancialCompany and Hell) kept me working constantly, such that I had virtually no free time, and when I did actually manage to get away from it for a couple of days, I was so burnt out that all I wanted to do was lie still and stare at a wall.

You might think this is a bad thing, but I took the opposite view: It was, in some ways, great that I didn’t have time or energy to spend money. Work was so immersive that I didn’t see the point in buying much. Let’s say I went out and got a brand new xbox 360 back in 2005 for $399, along with 10 games at $50 a pop and a couple of accessories. When exactly would I be able to sit down and play through the 300+ hours of gaming I’d just purchased?

Never — the answer was absolutely goddamned never, not while I was constantly working days and nights and weekends and holidays. Holding this thought close to my consciousness put a quick damper on urges to do stupid things with my dollars.

Odds and Ends

As I continued to optimize, I learned how to a) use the library instead of buying books and CDs for my personal and exclusive use, b) trade and borrow stuff with my friends (I’ll give you my Ocarina of Time if you give me your Mario Kart!), c) use clothes until they were actually worn out d) work out at home instead of paying for gym memberships, e) tell people to fuck off when they acted offended that I didn’t want to do something uber-expensive like rent a cottage in Tahoe for a 2-week ski resort vacation for “only” three thousand dollars.

And so on. You’ll develop your own list of things that you decide to change as you continue to turn the knobs on your personalized Retire Early dashboard.

Frugal Fatigue

More than just a cutesy-pie alliterative phrase to describe being tired of saving money, frugal fatigue is a real, bona-fide condition.

And that condition is usually underlying life fatigue, which somehow manifests consciously as being “tired” of not spending.

The thing is, many of the techniques described to save money also end up taking time and energy. DIY projects are a great example. Perhaps you’re cleaning your own carpets instead of calling a service. This project may require you to go to an equipment rental place, schlep an ultra-heavy steam vacuum home, run it across carpets for several hours (all the while adding detergent and changing water) before finally returning it to the rental place. Now you’ve saved a hundred bucks or more, but you’re also tired and exhausted and half-wet and it’s time to eat, and well, you do all your own cooking now, so you’ve got to keep moving. And after that there’s laundry and whatever the hell else you have going on.

You get the idea. Too many weeks in a row like this, where you’re stretching yourself thin to get household stuff done by virtue of your own personal blood sweat and tears, and you may be getting burnt out.

And when you start getting burnt, fantasies often follow in tow: My life would be so much easier if I just paid the money to have someone cut my yard. Or if I could just go out to eat tonight. Or have a cleaning service come by the house tomorrow.

You may start blaming your new, non-spendy life for your personal sense of tiredness. You may start feeling deprived again. (In fact, one way to describe frugal fatigue is a low-level feeling of overall deprivation and need.)

Here’s what I’ve personally handled it when an episode hit.

- I increased efforts to be mindful. Reminding myself that my work fatigue was (usually) greater than frugal fatigue helped me to see that it was worth it to continue on the same path. In this context, the frugal fatigue becomes practically meaningless. If you are sick of working — or working is making you sick — then it’s usually worth it to stay on the path even if you’re kind of tired in the moment. In other words, the act of working itself made me personally feel deprived (of my life! of my time!) much more so than the lack of spending.

- I went ahead and spent some money that my brain was telling me would make me happier. For example I’ve paid landscapers to mow my lawn once in a while to free up a weekend to travel somewhere. Or I’ve ordered a pizza on a night when I’m doing work around the house, with the mindset that this is still much cheaper than paying someone else to do that work I’m doing (fixing the toilet, whatever). These sorts of compromises can help take the edge off.

- I renewed focus on personal care. During one bout of frugal fatigue, I was complaining to my wife about “all of the bloody work around the house that just never, ever ends” and she cut through my inane bitching with a comment: Are you getting enough sleep? And I was dumbstruck by her insight: No. I hadn’t been. A week of making sure to get 8 hours a night fixed things. Everything in life seems more difficult when you’re not getting enough rest and/or not exercising at all. (Along with getting enough sleep, exercising helps to relieve stress, elevating mood and making life seem much easier.)

You may also find — particularly if your frugal fatigue is persistent and will simply not go away — that your budget is simply too low. If this is the case, consider performing more extensive analysis of the situation and building more spending back into your life. Write down the things that you want to spend more money on, and why.

Then do some of them.

Do you feel better? If yes, these things should be part of your permanent budget — raise it. Seriously. Do it. You don’t get a medal for retiring an extra year or two early.

You are not a cat. You only get one of these, you know. Lives. It’s important to have a life you are happy to live, including during your accumulation phase. Ask yourself if you were hit by a bus tomorrow if you would have regretted “not spending your money.” If the answer is yes, consider the possibility that you’re spending below your own ideal set point. Your own levels of spending should allow you to buy whatever you want. Because if you’re successfully navigating the adjustment to becoming a saver, you are actually eliminating many of your wants because you’ve realized they’re not necessary for your overall levels of happiness and well-being.

Look, it’s not good if you always feel you’re doing without. Committing to being financially independent should not feel like signing up for a half a lifetime of misery so you can have half a lifetime of awesome.

Last note on this subject: If you never feel frugal fatigue, you’re either an absolute genius (you are living your life exactly in accordance with your values and desires and therefore never feel deprived) or you haven’t yet tried to cut too much. Drop your spending some more and see what happens — maybe you’ll be just as happy, and you can remove additional years of working from your future.

Value Changes

Something unexpected happened to me after a couple of years of being on this whole saving and investing journey.

a) I lost interest in talking about most things (read: stuff, AKA items existing in the physical world).

b) I realized just how much time other people devote to this very activity.

c) I became increasingly incredulous upon hearing that somebody was about to spend a bunch of cash on something I thought was probably ill-advised, like a 6K family cruise, or a 1 million dollar McMansion 60 miles away from a place of employment.

d) I began to increasingly value efficiency and sustainability.

The behavioral changes I’d undergone had somehow altered my preferences as a person; I didn’t merely stop spending money — I also lost interest in people who spent a lot of money. (Or, at the very least, people who can’t talk about anything other than their latest purchases — people who define themselves nearly entirely by things. People who think their success in life directly equates to their levels of spending. People who are obsessed with status. Gawd!)

And I’d managed to cultivate, if not disdain, then at least a fair amount of confusion when it came to evaluating other folks’ personal spending choices. It became increasingly hard for me to accept how little your average person thinks about money, especially given that I thought about my own spending quite consciously.

I don’t think any of these things are particularly bad changes. But it’s worth pointing out that these were unintended side-effects as a result of my own quest to become a saver.

Back to the Present

After two hours of nearly continual talking, with only occasional breaks in the action when my friend had questions and comments, I looked around the table to find our dinner gone, plates cleared, darkness outside the windows of the restaurant. I had completed describing the transformation. There was nothing left to cover.

Well, shit. That sounds like awful lot of work.

Depends on your point of view. Truth is that after a while, I came to see it as a form of play, rather than work. The game was: How can I adjust my lifestyle and thought patterns in such a way that I wind up happier saving instead of spending? And the side benefit ended up being, of course, becoming rich, which is really just code for having increased options in life. Like, say, quitting my job to pursue more meaningful and interesting activities.

Do you think it’s all been worth it? All of the effort required to do what you did?

You know, it wasn’t a lot of effort. There’s a small transition period when you make the change, and after a while, that change becomes normal. Like traveling from sea-level to high altitude. The first month you feel it — a bit lightheaded, maybe dehydrated from the reduced moisture in the air. You get a bloody nose or two. Then your body adjusts and it’s like you never made the move at all. I thought I made that clear?

Still. You know what I mean. Based on the fact that you were able to talk about it for two straight hours, you clearly put a lot of thought and energy into the transition — into learning to spend less and save more.

I hesitated before answering, thinking about the last couple of months. (I haven’t been working since mid-April of this year.)

I recalled a few delicious mid-day naps. A re-reading of the first three books in the Game of Thrones series — 2600 pages or so of pure terrific. Relaxed evenings with my wife. A total and complete absence of dread. (Here I’m referring to the fierce sense of disappointment and unease that descended each and every Sunday evening as I contemplated the start of yet another another stupidity-filled week of obligation at the ‘ol office.)

Then a specific memory surfaced. A few weeks ago I’d taken off to a neighboring town to watch the older of my two nephews graduate from elementary school at eleven o’clock in the morning. He didn’t know I was going to be there, and when he noticed me in the audience, arms flailing wildly in a mad attempt to draw attention to myself, his surprise was priceless. Then, after the ceremony, his parents had to go back to work, but I didn’t. So we stayed on the gray asphalt lots around the school, splitting time between basketball, foursquare, and randomly chasing one another as we waited for his younger brother to be released a couple of hours later. If you weren’t here to sign me out, I woulda had to go back to class, he told me, thrilled by his unexpected escape.

These are the things I was never able to do while working.

But it’s not just that. It’s everything. Having an abundance of free time has changed my perspective on activities that used to cause me some amount of grief — like devoting a full day to visit my aging mother or paint a couple of rooms of a friend’s house. I used to think: Sheesh, I get so few days off work, and this is how I’m filling the hours?

Now I think: I want to help these people in my life, and I have plenty of available cycles to do so. I can help them out and still have gobs and gobs of time left over for myself and for my wife — to veg out and play a video game or go outside for a hike. I don’t resent these duties anymore. They feel like play. It’s just life now — my relaxed, uncomplicated life.

And this is what I hoped for beyond everything else when pursuing my early retirement dreams. I’d hoped beyond hope that the new lifestyle would allow me to be a better person. A happier and more present uncle, son, friend, husband. And I realized that’s exactly how it’s going down.

I used to visualize the months of my working life cloned, copied and pasted into infinity until a final system crash. (That’s geek-speak for “until I die.”) And in the interest of keepin’ it depressingly real, I’ll state that that particular idea invoked an inky pool of pure despair, along with a sense of stark hopelessness. (Thanks for that, brain!)

But as my friend waited for my response to his question — Was it worth it? — I instead pictured the last few weeks repeated into infinity. They passed through my mind in an instant: the freedom, the luxurious sense of being fully rested and awake, the personal choice, the ability to pursue what I want when I want — particularly the fact that I can plug into peoples’ lives whenever they might need me, or I might need them, with hardly any reservations when it comes to the most precious things I have to give: my time, my energy, my deranged sense of humor, my optimism.

The answer to his question appeared so self-evident — the fight between yes and no so absurdly one-sided — when I finally responded, I felt a great deal of surprise he felt the need to ask it at all.

This was a fantastic read. Congratulations on your success and early retirement! Your story is truly inspiring. I am 29 and have decided upon reading this to immediately implement some of your saving techniques. I am not exactly starting from “zero”, but could kick it up another notch. I’m about to do some serious blog reading….all the best.

-Ross

Your experience might help my other half, who experiences frugal fatigue. She likes the goal of having more time. I am fairly frugal (not as much as MMM or ERE). While I am fully on board, I try not too push my other half and friends too much. The length and details of your post are appreciated.

Pingback: The Art of Frugality

Great article, very well written. Should be a must read in every high school in the country.

Work is the reason why I’m aiming for FI. Only I’m 49, not 29, and while I’ve always been a saver (I was at 0.2 five years ago), it’s got me to 0.4 of my goal when I need to get to 1.0. And now work, which should be awesome but isn’t because of tiny red tape details that are driving me crazy.

New boss, a/k/a old coworker, is suddenly freaking over things that don’t matter. I had a project, two weekends ago that became all-consuming. Not my fault, a project I wasn’t in control of went sideways because the hardware was OLD and when you upgrade code on old hardware, you hit bumps. And I was pleased by my efforts, but the time involved was 3x the guestimate. And this means it violated a rule that said if you go over x hours of OT you need to take that time off BEFORE you work the OT.

And I did. I took the guestimated time off, but not the full amount of time worked because 2/3rds of that was unexpected. And the boss went off on me for it. And now I have this same project, replicated on another set of OLDER hardware, for this weekend. It’ll suck, but once this project is over, I won’t have to sweat this project for the forseeable future. I want it over and done with. But there is no way to take the revised-guestimated time off beforehand as I am looking after mine, another vacationing coworkers stuff, and another coworkers stuff who fled our area and got himself a job in a different area. Surely Boss’d understand, right, and let me take the time off afterwards?

He’s already sent out several emails emphasising that all OT over x hours must be taken in advance. And he knows that this weekend will involve a lot of OT. So I’m thinking the answer there will be a ‘no’.

Did I mention the headcold I’m currently enduring?

Jesus H Christ, but I am not being paid enough to deal with this irrelevant shit.

So now I’m considering quitting with only 0.4 instead of the 1.0 and jackass can find someone else to work the weekend and the rest of the week.

Thanks for letting me vent. Consider this missive whenever you start to think, ‘boy I miss the bad old days.’

Just sent him an email asking him to pick between my taking all of one day plus some of the next off, or some of two days. All sweetness and light, mind you. And now I’m taking my neo citreon (which is not a hot toddy no matter how much I want it to be one) and going to bed.

Maybe the lottery ticket will come in.

Pingback: The Financial Value of Honesty

why eat cbd gummies

where can you buy cbd gummies in pensacola fla